Text by Paolo Rumiz

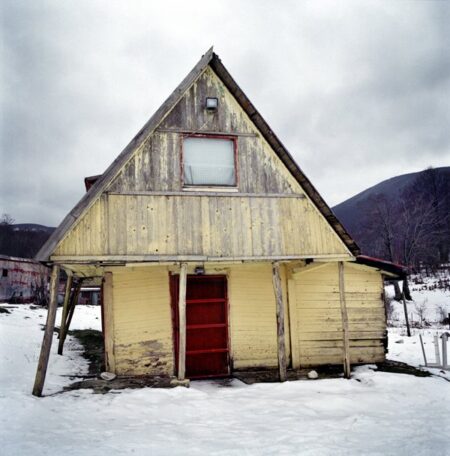

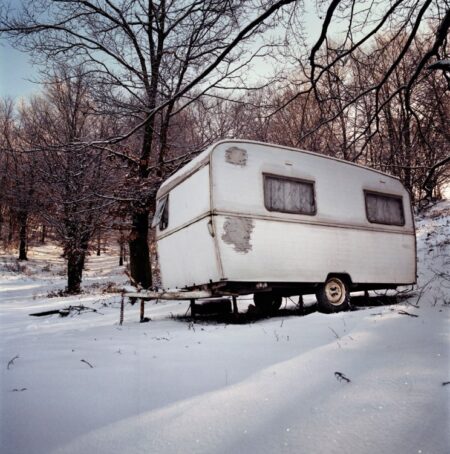

Il Matese, che Francesco Fossa racconta nel suo libro fotografico “Quota mille” mostra un’altra Italia, lontana secoli dalla Roma di oggi, lontana soprattutto dal mondo cellofanato che

imperversa in Tv. Un mondo solitario, abbandonato dalla politica, privato di ogni difesa, aggredito dai predoni dell’energia, dell’acqua e del vento. Un mondo di gente dura,

arroccato alle sue montagne e che si difende come può, anche ostentando l’orrido ai forestieri.

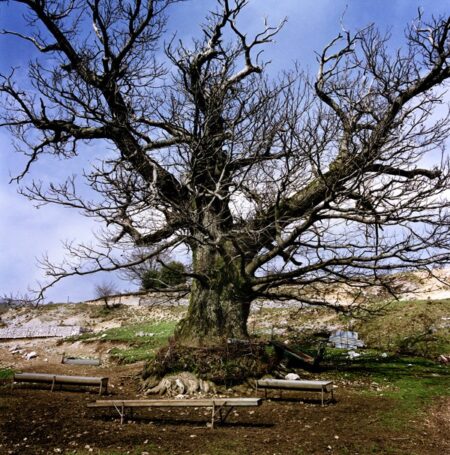

Nel mio viaggio in quei luoghi ho visto gole senza fondo, strade che si infilano senza nemmeno lo spazio per i paracarri; curve a picco sul nulla come nelle illustrazioni dantesche del

Doré, insegne che additano il Saloon dell’impiccato o valloni arcigni come la Bocca della Selva.

Fotogrammi incancellabili nella memoria, come quelli – di forza quasi neorealista – che compaiono nel libro di Fossa.

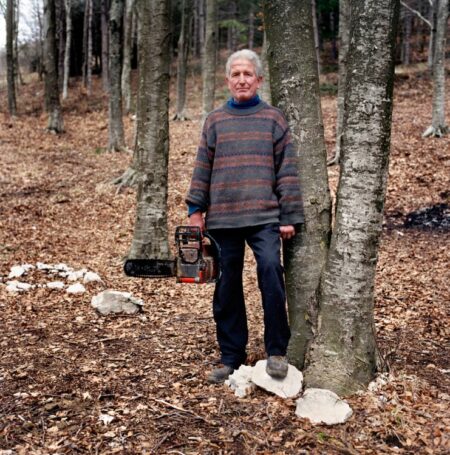

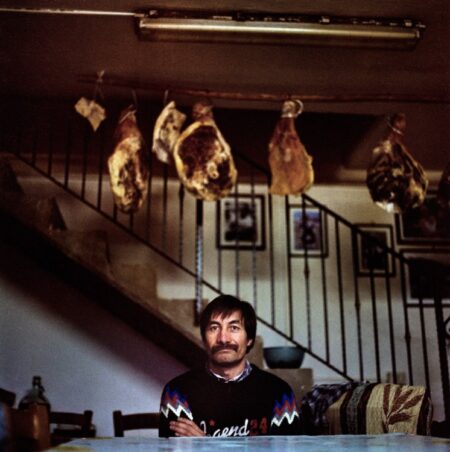

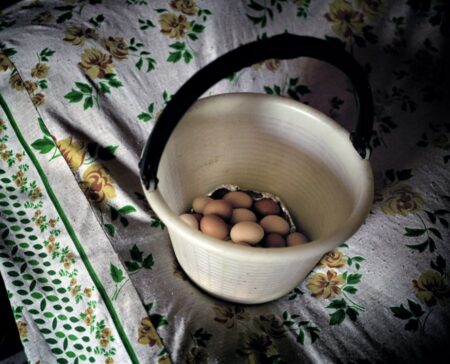

L’Italia non ama i montanari, li considera cafoni, burini, bestie ignoranti. L’Italia vive a quota zero, ignora che a quota mille si è giocata fino a ieri la sua storia

e si è costruita la sua ricchezza pastorale.

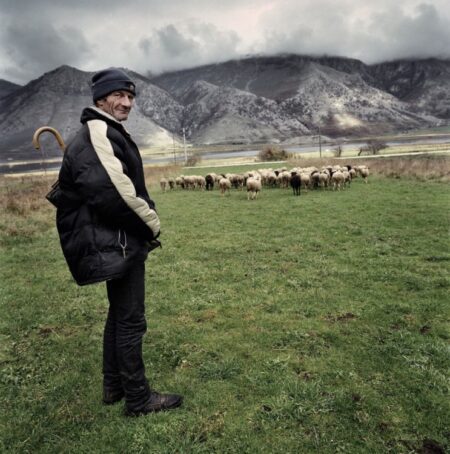

Non esiste nel Mediterraneo un luogo simile, con la montagna così vicina al mare (anzi, a due mari), un luogo dove di conseguenza la transumanza si può giocare

in così pochi chilometri, senza i nomadismi estremi del Medio Oriente o del Nordafrica. E’ tempo di riappropriarsi di questi luoghi, di guardarli con fierezza, con orgoglio.

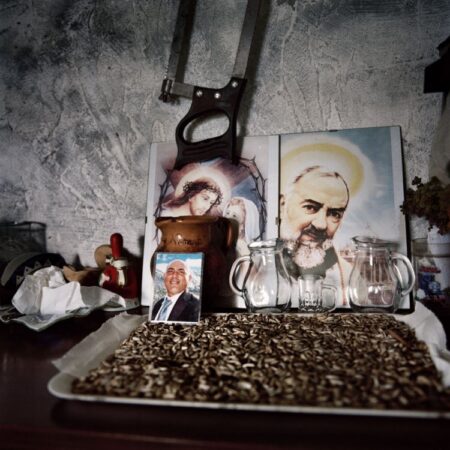

Sono questi uomini e queste donne, fotografati da Fossa – che rappresentano la nostra memoria, il nostro legame antico alla terra e al paesaggio.

The Matese, which Francesco Fossa recounts in his book “Quota Mille” shows another Italy, centuries away from the Rome of today, far from the cellophane

world that invades our television screens. It is a solitary world, abandoned by the center of power, defenseless, invaded by the pirates of the energy,

water and wind businesses. It is a world of hard people, perched on their mountains, who defend themselves as best they can, even petrifying the outsider

with their often horrid state.

During my trip, I saw “bottomless gorges, narrow streets; steep curves that cascade into nothingness like Gustave Dore’s illustrations of Dante;

signs that point to the Saloon of the hanged or surly canyons like the Bocca della Selva.” These images – like those that appear in Fossa’s book – cannot but be indelibly

inked in one’s memory. Italy does not love mountain people; it deems them ignorant, rednecks, beasts.

Italy lives at sea level, not realizing that her history has played out at a far higher

altitude and is based on her pastoral richness.

There is no other place like this in the Mediterranean. There is no other mountain so close to the sea – in fact two seas – and where migration from highland

to lowland happens in a few kilometers and without the nomadic journeys of the Middle East or of North Africa. It is high time to make these places ours; to regard them with pride.

These men and women – photographed by Fossa – represent our memory; our ancient ties to the land and to this country.

Paolo Rumiz